|

||||||

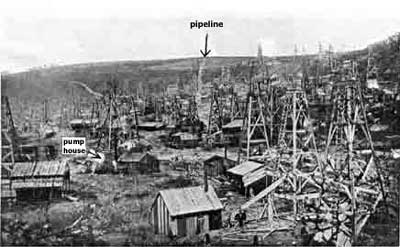

The Pipeline War

Yes, it was a WAR. There were attacks on persons and property, shots, injuries and death, raging fires set by arsonists, great damage and destruction, infiltration at night, propaganda, dirty politics, extortion, loss of money and most of the rest that goes with war. It was also a war of wages and rates. It was a series of battles fought in Oil Creek Valley and at Pithole, and it pitted the teamsters against the pipelines. The pipeline war started in 1863 although there were rumblings before then. The Union was at war with the South at about the same time.

The teamsters had cast a wary eye on the first few attempts to lay pipelines and had hired agents or representatives to try to block any efforts to obtain charters from the Pennsylvania Legislature. They were fearful of losing their business. The teamsters' wrath escalated to overt action in the oilfields when they attempted to wreck the lines even when they were being laid.

Already well practiced by their wrecking activities at the Tarr Farm - Plumer pipeline and the Nobel Well - Shaffer pipeline, the teamsters really came out in force when in late 1865 Henry Harley, a commission dealer, commenced to lay two two-inch lines from Benninghoff City to his tanks at the Shaffer railroad yard, a distance of two miles. The lines ran into the very nest of the teamsters who lived or camped along the route, particularly at the town of Shaffer. The teamsters used their teams and heavy chains to pull the joints apart, virtually destroying the Harley pipelines. Harley, however, persevered, took precautions, and relaid the two pipelines completing the job in March, 1866. The teamsters were aghast when they learned that each two-inch pipeline could deliver up to 2000 barrels per day to the storage tanks.

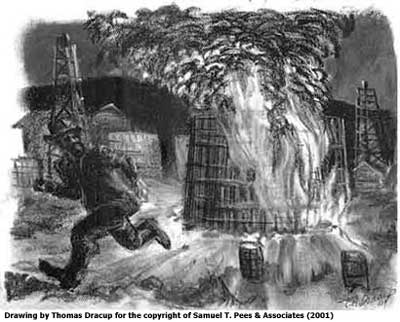

The teamsters threatened Harley's life and, at night, torched his large wooden tanks which were filled with oil. The massive, hissing oil fires created a frightful scene, panicking people unlucky to be in the vicinity. Besides the storage tanks, damage amounted to the loss of the shipping platform, four tank cars and the oil (Derrick Handbook, 1898). By this time it seemed that everybody was armed. The mob returned on another night in the wee hours and set more wooden tanks afire having threatened Harley's watchmen with death if they didn't leave. Many shots were fired in the air and pot shots were taken. A teamster was killed. Fear struck the hearts of oilmen working their wells in the valley and worry beset their families.

|

||

|

During this period of unrest, incendiary fires were set in Pithole, Titusville, Benninghoff Run, even Franklin, and there were fatalities particularly in the terrible conflagration along Benninghoff Run. Boiler and engine houses and other oilfield structures were close to residences in these hurriedly built boom towns, so when there was an oil fire homes would burn too. The townspeople of Titusville became understandably nervous about suspicious fires. A vigilance committee was formed there and their first act, as a warning, was to erect a gallows at a prominent site in the town (Derrick Handbook, 1898).

To counter this ongoing destruction and mayhem, Harley hired detectives out of New York who posed as teamsters but were actually collecting evidence which was used to arrest and convict twenty of the unruly crowd that had attacked his line. They were jailed in Franklin. Harley took in a partner and went on to lay more pipelines.

Van Syckel also had his share of problems with the teamsters while laying his two pipelines from Miller Farm and Meridith to Pithole in late 1865. They broke the joints with pickaxes and scattered the pipe (Giddens, 1938). In an effort to discredit the pipeline and its people, the teamsters posted signs on trees along the right-of-way condemning the pipelines and the management, even threatening them and warning that property would be destroyed. These tactics were designed to disrupt management and to make future clients at Pithole leery of sending their oil through the line. These placards were a manifestation of a practice already employed by the teamsters who fostered a negative word-of-mouth and rumor campaign through the oilfields claiming that the pipelines wouldn't work, that they were subject to leakage and that much oil would be lost by those using them. Many of the leaks which happened with a certain frequency were found to be man-made (Talbot, 1914).

Van Syckel ordered carbines from New York and hired men to patrol the line with orders to shoot if anyone attempted to damage the pipe. The sheriff was called in for extra measure. Although the teamsters still threatened the company officials "with transportation to a warmer climate", the pipe was laid on to Pithole. On October 10, 1865, its opening day, it proved an immediate success (Johnson, 1956).

|

Pithole had its share of incendiary fires during the pipeline war. |

Both the Harley and the Van Syckel pipelines displaced a large number of teamsters from the region which originally had employed about 6000 of them. The wooden barrel full of oil was the teamster's bread and butter, but these grew scarce as more pipelines were laid and the wagons began to return home empty. The pipeliners charged less than the teamsters did. This economic factor alone caused the demise of the barrel-laden wagons, but ease of handling and speed regarding pipeline delivery were also very important factors in the process.

![]()

| © 2004, Samuel T. Pees all rights reserved |

|