|

||||||

KNOCK KNOCK

The following is a digression, a sudden urge to skip around (historically). However, the viewer will see that a return to Oil Creek Valley in the year 1860 actually happens in this article.

Pinging

You may remember the pinging and knocking sound caused by the gasoline used by earlier automobiles. The knocks were like a series of shots under the hood and they definitely got one's attention. Another comparison would be the sound of popcorn popping under the lid in the old kettle. These knocks seemed to be at their worst when the car labored up a long, steep hill.

To briefly explain the cause of knocking, it is reasonable to start with detonation. Detonation is a spontaneous and extremely rapid combustion of the unused (unburnt) portion of the gasoline-air mixture in the cylinder. The concurrent sudden build-up of high heat and pressure, far beyond that of normal combustion, creates a shock wave which is heard as a ping or a knock and causes damage to the engine (James Bryant, 2001, written communication).

|

||

|

|

||

|

Anti-Knock Experiments

The first anti-knock additive was iodine. In a 1916 experiment in a Dayton, Ohio, laboratory, it was added to kerosene which was the fuel being tested at the time. Kerosene had a tendency to knock terribly. The iodine knocked out the knocks. However, in the end it wasn't found to be economically practical for gasoline motors. It was too costly.

The next anti-knock additive was aniline. A bank of technical knowledge was built up around aniline, even an anti-knock scale. However, aniline stunk so badly that the chemists gave up. This was followed by compounds of selenium and tellurium, but they smelled badly too (and the smell wouldn't leave the skin, hair or clothes).

Finally, in 1921, tetraethyl lead was found to be a powerful anti-knock chemical. It was used with other additives employing bromine or chlorine which helped to scrub out residual matter such as deposits of lead oxide in the engine.

The octane scale of zero to 100 was developed as a means of expressing whether gasoline will knock in an engine. A 100 octane gasoline was used in airplanes (no knock). Tetraethyl lead introduced into the gasoline increases the octane number.

|

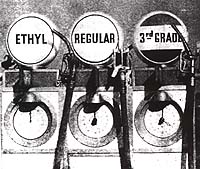

When my father drove into a filling station in the 1930's, 40's, 50's, he always asked for ETHYL. It meant high test by virtueof containing the ethyl anti-knock compound. In 1935 ethyl cost about 2¢ more per gallon than regular gasoline, but it didn't ping. Of course, many gasoline brands had an ethyl pump in those days. Examples are Pennzoil, Sinclair, Cities Service, Gulf, Mobilgas, and many more. The pumps in the above illustration dispensed two grades that probably knocked and one high test (ethyl) in the early 30's (the brand isn't specified). A lot of brands with ethyl had names that disappeared decades ago. |

The tetraethyl lead was added to the gasoline at the refineries. Remembering the famous iodine experiment and the reddish color of the kerosene after the iodine had been added, Ethyl gasoline was dyed red so that it would be recognized as Ethyl. It was first sold at a gasoline station of the Refiners Oil Company in Dayton, Ohio, 1923.

|

||

|

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) asked for a phasedown of lead in gasoline in 1972. This was fought in the courts but upheld in 1976. Unleaded gasoline and the catalytic converter forced a change on Ethyl in the United States. The company then concentrated on other additives, most being petroleum or fuel and lubricant related, and it diversified. Ethyl has been no stranger to the Fortune 500.

Ethyl's Oil History Collection

Ethyl Corporation added a milestone to the history of oil products with the compounding of the anti-knock chemical. The company took great interest in collecting paper memorabilia of the oil industry. They also produced films about fuel knock, gasoline management, fuel economics and other topics.

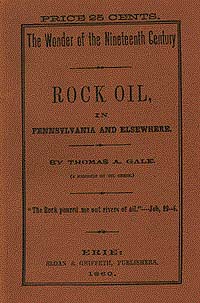

In 1952, Ethyl undertook the reprinting of a rare 1860 oil booklet ROCK OIL by Thomas Gale. The reprint was a solid contribution to oil archives and oil historians. The original was printed like a pamphlet and sold to first comers at Titusville and at rail stations. It was fragile. Ethyl Corporation faithfully reproduced the original and then incorporated it in a splendid book-like container. Explanatory notes by Dr. Paul Giddens of Meadville, E. Degolyer of Dallas and Ernest Miller of Warren are in a slip component of the container. This facimile edition has become a treasured collector's item on its own.

|

At 25¢ per copy, Gale may have made a tidy sum from this booklet. The demand was there at the time. It is said that only three original copies are now known to exist. The cheap newsprint didn't last long. Gale lived in Riceville on Oil Creek, but that place was north of the prolific, shallow oil belt for which the lower half of Oil Creek is famous. |

Gale gave first-hand accounts of wells at the time, for instance the Barnsdall-1 which was the first successful producer after Drake's. Only a few wells had been drilled in the Oil Creek area when Gale took up his pen. Nevertheless, his 80 page booklet must have been eagerly sought by the horde of would-be oilmen crowding into the oil towns and probably was their first primer on oil.

In 1959, for the centennial of the Drake Well, Ethyl Corporation exhibited its collection of oil memorabilia including rare books at Allegheny College, Meadville, Pennsylvania. The college is only 29 miles (46.4 km) northwest of Col. Drake's first oil well near Titusville. Allegheny had a history of interest in oil. It was an Allegheny history professor, Dr. Paul H. Giddens, who became the first curator of the 1934 Drake Well Museum and who wrote several books on early oil, including "The Birth of the Oil Industry". He encouraged the Gale reprint.

It is interesting to note that in 1962 the Ethyl Corporation was acquired by Albemarle Paper Manufacturing Company. The paper company then dropped its own name in favor of Ethyl, actually Ethyl Corporation (Virginia). According to stock market analysts, Albemarle was "spun off" in 1994.

Concluding Remarks

The high reputation of Ethyl and its chemists has always impressed me. It is well deserved.

The reason for this article dates to an occasion when I was redrafting the plans of a refinery which had been destroyed by fire in 1970 (Amalie Refinery at Franklin, Pa.). The plan showed the spot where Ethyl was introduced into the gasoline process. That occurrence and advertisements mentioning Ethyl kept the subject on my mind. Finally, I have written it away.

Bibliography

Leffler, W.L., 1979, Petroleum refining for the non-technical person, The Petroleum Publishing Company, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 159 pages.

The Oil and Gas Journal - The Oil City Derrick, 1934. Why Ethyl Gasoline is Cheap at 2¢ a Gallon Extra. Diamond Jubilee of the Petroleum Industry, Aug. 27, 1934, pages 10 to 11.

Oil and Gas Journal, 1959, Petroleum panorama, 1859-1959, Vol. 57, No. 5, Jan. 28, 1959, pages F-32 to F-33.

Robert, J.C., 1983, Ethyl, A history of the corporation and the people who made it, The University Press of Virginia, 448 pages. Robert's book recounts the history of the Albemarle Paper Company and Ethyl Corporation. It is a good reference on the people of Ethyl and their chemical experiments.

William, H.F. et al, 1963, The American petroleum industry, the age of energy 1899-1959, Northwestern University Press, Evanston, 928 pages.

Additionally, numerous advertisements and papers in the author's collection.

| © 2004, Samuel T. Pees all rights reserved |

|