Editorial and PHI Symposium Report – Bradford, Pennsylvania, June 19-21, 2014,

Greetings from Oil Country: Shared Images of a Burning Oil Tank Across Five States,

Samuel Downer and The Downer Kerosene Oil Company,

Of Kentucky, Salt, and Oil: A History of Early Petroleum Finds Along the Cumberland River,

Early Texas Oilfield Photographers,

19th Century Russian Petroleum From Baku: The American Perspective,

Claims of Priority: Spindletop vs Baku,

The Avant-Garde in Petroleum: Franco-Algerian Oil Cooperation, 1962-1971,

History of Petroleum Exploration in Yemen,

Abstracts: 2014 Oil History Symposium & Field Trip, Bradford, Pennsylvania, June 19-21, 2014

Petroleum History Institute 2014 Awards

Crawford Family Historical Marker,

Book Reviews

Comment and Reply

Memorials

Bibliography of Petroleum History 2012-2014,

Volume 15, 2014 Abstracts

Editorial and PHI Symposium Report – Bradford, Pennsylvania, June 19-21, 2014

Rasoul Sorkhabi

ABSTRACT: This paper serves as editorial to this issue of Oil-Industry History as well as a brief report on PHI’s activities in 2014 including its annual Oil History Symposium and Field Trip held in Bradford, Pennsylvania. This report is in continuation of the annual reports prepared by Dr. William Brice in the previous issues of Oil-Industry History (Brice, 2005, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2013).

World War Ii Tank Truck Industry Support: An Army Might Move on its Stomach, But Everything Else Moves on Oil

John L. Conley

ABSTRACT: Prior to the World War II, ocean tankers moved over 95 percent of the oil shipped to the East Coast from the U.S. Gulf Coast. That supply link was seriously disrupted by German U-boats which found the slow moving tankers an easy target. The demand for alternative means of petroleum transportation utilizing rail, truck and pipelines was met through the combined efforts of government and industry. Transportation was never nationalized and intense intermodal competition was sidelined. Much has been written about how the oil and railroad industries adapted to wartime distribution. This paper will examine the role of tank truck transportation in support of the nation and the war effort.

The tank truck industry faced both regulatory and resource challenges in adjusting to its wartime role as primary domestic distributor of petroleum products to citizens and to the various industries to produce goods and services to support the war effort. Oil transports ran around the clock to provide aviation fuel to airfields not served by rail. The regulatory challenges were met in part because Interstate Commerce Commissioner Joseph B. Eastman served as Director of the Office of Defense Transportation (ODT) from December 18, 1941 until his death in March 1944.

Perhaps the most important rule was ODT Directive #7 which provided that tank trucks be used in petroleum movements of less than 200 miles. This freed up the aging tank car fleet to move oil longer distances. One estimate reported by the Petroleum Administration for War (PAW) was that one truck transport released an average of seven tank cars from short haul service. Tank trucks were at the top of the list of materials approved for construction from precious metals such as steel and aluminum and, perhaps more importantly, for tires.

Eventually, the standard 2,000-gallon tank trailer was increased in size up to 8,000 gallons and states were urged to waive size and weight laws. On the human side, tank truck drivers were eligible for deferments as their skills were needed to move petroleum. The petroleum industry, from exploration to refining to distribution, helped win the Second World War. Skillful adaptation of the tank truck as a tool of oil transportation contributed to that success. At war’s end, the Army-Navy Petroleum Board of the Joint Chiefs of Staff said: At no time did the Service lack for oil in the proper quantities, in the proper kinds, and in the proper places.

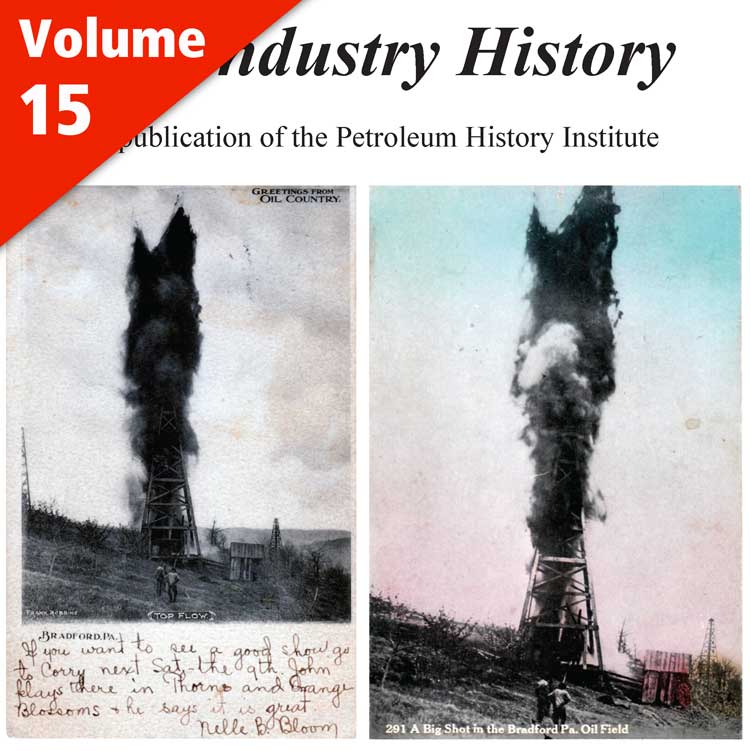

Greetings from Oil Country: Shared Images of a Burning Oil Tank Across Five States

Victoria Manning and Jeff Spencer

ABSTRACT: Images of the early oil industry were commonly used in postcards and there are several notable instances of a single image being shared by multiple locations. The Greetings from Oil Country project by Victoria Manning explores one unique and wide-ranging occurrence of this location sharing by fifteen different cities in five different states: Wellsville, Bolivar, and Olean in New York; Bradford, Kane, Warren, Titusville, Oil City, Clarion, and Franklin in Pennsylvania; Findlay and Lima in Ohio; Tulsa and Muskogee in Oklahoma; and Beaumont, Texas. Through examining the oil history of the most probable locations of the burning oil tank, the postcards themselves, contemporary newspaper descriptions, books, stereoviews, souvenirs, and the work of oilfield photographers, the co-authors show the tangled nature of these shared images and the difficulty in extracting definitive evidence.

Robbing Peter to Pay Paul: The Story of New Sheffield and Shannopin Fields, Beaver County, Pennsylvania

John A. Harper

ABSTRACT: The New Sheffield gas field was discovered in 1884 on the John Zimmerly farm in Hopewell Township, 1.5 miles west of what is now Aliquippa, Beaver County, Pennsylvania. Some wells in the field had open flows exceeding 15 million cubic feet of gas per day (Mcfgpd) from a reservoir called the Shannopin sand, a persistent, westerly extension of part of the Hundred-Foot sand at the top of the Upper Devonian Venango Formation in southwestern Pennsylvania. The New Sheffield field eventually became the largest and most important gas field in the county as gas was piped to towns as far away as East Liverpool, Ohio, and New Cumberland, West Virginia, for residential, commercial, and manufacturing purposes. A year after the discovery of New Sheffield field, oil was discovered at Shannopin, a small Ohio river town on the southeast flank of the gas field, opening the Shannopin oil field. Some of the wells drilled in the main part of the field, near the village of Gringo a few miles southwest of Shannopin, flowed at rates exceeding 1,000 barrels of oil per day (BOPD). Production was strong for a few years, with wells producing as much as 400 or 500 BOPD from the Shannopin sand. Gringo became an instant boom town, while Shannopin flourished as a result of its location as both an Ohio River landing and a station on the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad.

A spate of new pipelines and an increase in consumption eventually led to overproduction of natural gas in the field. New Sheffield production began to decline within two years, and by 1905 the field was virtually abandoned. Similarly, overproduction of oil and a resulting lack of rock pressure resulted in Shannopin field beginning to decline as early as 1889. Repressuring of the reservoir by injecting natural gas began in 1913, which tripled production in some wells, but the field continued to decline. Although a handful of wells continued to produce in the Gringo area into the 1990s, the field is now abandoned. It has been speculated by many that the decline of both fields, occurring within a few years of their discoveries, resulted from overproduction at both ends of the same reservoir. New Sheffield field is structurally up-dip from Shannopin field, and the existence of oily gas near the boundaries of the fields suggests a porosity/permeability connection between them. Up-dip, wild drilling and commercial overproduction of gas from the structurally higher New Sheffield field probably helped drain Shannopin field of its natural gas drive. Down-dip, production of oil by natural gas drive probably helped exhaust the New Sheffield field ahead of its time, resulting in a sad case of mutually assured depletion.

Samuel Downer and The Downer Kerosene Oil Company

Neil McElwee and Lois McElwee

ABSTRACT: Samuel Downer was a quintessential, mid-nineteenth century American capitalist. Not averse to risking his entire personal fortune, he boldly seized one of the great entrepreneurial opportunities of his day, coal oil and petroleum refining, and made the most of it. In doing so, Downer realized the full promise of the new industry. He led the spectacular commercial growth of the coal oil refining industry and the eventual full scale transition from coal oil to petroleum-based refining. The refined products from his enterprises changed the way people in North America lived their daily lives and contributed materially and directly to the industrial growth of North America and Europe. By 1860, the Downer Kerosene Oil Co. was the largest manufacturer of kerosene in North America. Unlike most other large refiners of the period who concentrated on maximizing kerosene production yields, the Downer organization made nearly every product then possible from a barrel of crude. The Downer firm revolutionized the lubricating industry.

Devising the best distilling and chemical treatment methods and early innovations like cracking in the late 1850s, the Downer Kerosene Oil Co. became the standard of excellence in the young refining industry. In the 1860s new and radically different products like deodorized, neutral lubricating oil and mineral sperm oil enhanced the firm’s reputation for technological leadership and excellence. Additionally, Downer successfully manufactured these new products on a large commercial scale and sold them with similar success to the consuming markets of North America and Europe. Downer was a larger-than-life entrepreneurial force, a legend in his own time and one of the great pioneers of the early oil industry.

Of Kentucky, Salt, and Oil: A History of Early Petroleum Finds Along the Cumberland River

Brandon C. Nuttall

ABSTRACT: Kentucky’s pre-1859 petroleum history is rich but largely unknown. This article provides accounts of early boring and explorations, particularly for brines for the manufacture of salt that instead found commercial quantities of oil. The discovery of early salt springs led directly to the drilling of two important Kentucky wells: the Beatty oil well (1818) and the Old American Well (1829). The production and attention these wells attracted led directly to Kentucky’s post-Civil War oil boom.

Early Texas Oilfield Photographers

Jeff Spencer

ABSTRACT: Commercial photographers captured many views of early Texas oil booms. Common scenes included oil gushers, oilfield fires, fields of wooden derricks, and boomtowns. These photographs were produced and sold, often as real photo postcards (RPPCs). Many of the early photographs and postcards have no identifying photographer name on the picture side or on the reverse, but a few photographers did include their names and several of these men were active in specific geographic areas of Texas in the early 1900s.

Benjamin Harrison Loden (1870-1926) was the founder and owner of Loden’s Studio in the North Texas town of Electra. His work appears to be generally limited to scenes from the town and the Electra oil field. One Loden photograph from the nearby Burkburnett oil field has been located. His postcards include oilfield fires, derricks, gushers, and a missionary group ready to venture into the Electra oilfield.

Frank J. Schlueter (1874-1972) and his wife, Lois, opened a photography studio in Houston in 1907 or 1908. Schlueter captured scenes in at least sixteen Texas Gulf Coast oil fields and the Vinton oil field in nearby southwest Louisiana. Though perhaps best-known for his oilfield photography, Schlueter also documented the growth of Houston and the surrounding area’s industries and agriculture until his retirement in 1964 at the age of 90. Schlueter’s work includes some excellent panoramic photographs. Hundreds of Schlueter’s photographs are preserved at the Houston Public Library as the Schlueter Photographic Collection.

Two additional Texas oilfield photographers active in the Houston area were F. (Frank) G. Allen (1882-1921) and L. (Lester) L. Allen (1875-1949). These contemporaries are not thought to be related. Frank, formerly a New York newspaper photographer, photographed scenes in Goose Creek, Humble, West Columbia, Damon Mound, Hull, Blue Ridge, and Pierce Junction oil fields. Frank may have had a studio for a brief time in Shreveport, Louisiana where he produced and sold photographs of the nearby Caddo Lake and Homer oilfields. Like Schlueter, Frank Allen produced some stunning panoramic photographs.

L. L. Allen captured images in the 1920s of Raccoon Bend, Orange, West Columbia, and Spindletop (second boom) oil fields. He also ventured a very short distance into Louisiana, capturing scenes at the Hackberry oilfield. Census records list him living in Houston in 1910 and the Texas towns of West Columbia (1920) and Orange (1930).

Ralph R. Doubleday (1881-1958) is known for his rodeo photography, earning him the title, Rodeo Postcard King. He produced over 30 million postcards, many sold at Woolworth Five and Dime stores. Though he is generally not known for his oilfield photography, he produced many excellent postcards from west and north Texas oilfields and towns, including Burkburnett, Ranger, Breckenridge, Borger, Yates, Pecos, Texon, and Pioneer. He also visited east Texas and photographed some of that area’s boomtowns and oil fields.

19th Century Russian Petroleum From Baku: The American Perspective

Raymond P. Sorenson

ABSTRACT: Following the Drake well discovery in 1859, the United States dominated world petroleum markets through the rest of the 19th century, with production coming largely from Pennsylvania and other Appalachian states but with significant contributions from the Midwest (Lima-Indiana Field) in the final two decades. The only significant competitor was Baku, along the western shore of the Caspian Sea in Russia (now the Republic of Azerbaijan), where production dating back for centuries began accelerated growth in the 1880s that surpassed the United States by the end of the century, based on statistics from the work of Samuel Peckham (1884) and USGS publications (1883-1900). Baku’s new prominence was highlighted by some of the most spectacular flowing wells of all time.

Americans were well aware of Russia’s increasing influence in the international petroleum trade, but had little knowledge of the Baku oil fields. American petroleum industry publications usually provided only limited coverage of Russian activity, and United States governmental reports generally focused on international trade aspects. Most English-language publications with detailed coverage of the Russian petroleum industry were from European sources and dated from the mid-1880s or later. The books from important British authors, such as Marvin (1884), Redwood (1896), and Thompson (1904), were accessible to the domestic petroleum industry, while there is little to suggest that Americans had any knowledge of exceptional works by Russian authors, such as Goulichambaroff (1883).

Claims of Priority: Spindletop vs Baku

Raymond P. Sorenson

ABSTRACT: On January 10, 1901, the Lucas “Gusher” near Beaumont in southeastern Texas opened the Spindletop Field with an oil flow rate an order of magnitude greater than from any well previously drilled within the United States. It demonstrated the prospectivity of salt domes, introduced the Gulf Coast as a major petroleum province, radically revamped the corporate and economic climate of the petroleum industry, and generated publicity to match anything that had been previously seen. Without question it was one of the most important and influential wells in history.

Over the course of more than a century, the significance of Spindletop has continued to be recognized, but in some respects the accuracy of its history has been compromised. Early reports acknowledged that the Russian (now Republic of Azerbaijan) oil industry near Baku, along the western margin of the Caspian Sea, had previously encountered comparable or greater oil flow rates, but Spindletop enthusiasts today commonly ignore the Baku activity and erroneously claim that the Lucas well was the world’s first to flow in such quantities.

The Avant-Garde in Petroleum: Franco-Algerian Oil Cooperation , 1962-1971

Mattie Wheeler

ABSTRACT: Leading up to the 1973 oil shock, there was a period of more gradual but significant changes in the oil industry. This period in the 1960s and early 1970s can be characterized by two ruptures in what seemed like a stable Cold War system. First, the efforts of Western governments to maintain a corporatist system where the interests of governments and companies were in sync began to seriously unravel; spheres of influence did not constitute a good fit for global corporate interests. Second, economic changes coupled with revolutionary nationalism empowered and emboldened the oil-producing nations. Together, these factors caused fissures in the international system that finally came apart in the high drama of the 1970s. In this paper, I analyze France and Algeria as early examples of disruptors of the system during the 1960s. I begin with a brief history of the discovery and early exploitation of petroleum in Algeria during the Algerian War for Independence in the 1950s. I then discuss the shifting framework of Franco-Algerian oil cooperation in the 1960s with a focus on how this cooperation empowered both countries to build up their national oil capacities and challenge the status quo. Finally, I conclude with a close examination of the final Franco-Algerian petroleum negotiations of 1969-1971 and their ultimate conclusion: Algeria’s nationalization of its entire oil

industry.

History of Petroleum Exploration in Yemen

Mustafa As-Saruri and Rasoul Sorkhabi

ABSTRACT: The year 2014 marked the 30th anniversary of the first commercial oil field discovery in the former North Yemen; the discovery well being Alif-1 drilled by the American company Hunt Oil in the Marib sector of the Sab’atayn basin onshore Yemen. This was followed in 1986 by the discovery well West Ayad-1 in the Shabwah sector of the Sab’atayn basin in the former South Yemen by the Russian company Techno-Export. Although Yemen, due to political reasons, was the last Middle Eastern country to assert itself on the world’s petroleum map, geological studies and exploration activities in Yemen date back to the early 20th century. This paper summarizes the history of oil exploration in Yemen, especially chronicling the growth of the country’s oil industry and activities in the past four decades. We first describe the exploration history in 10 sedimentary basins of Yemen, then present a chronology of the exploration (1910-2013), and finally give a bibliography of 187 publications on the petroleum geology of Yemen. Nearly 40 percent of these papers were published in the 1990s, soon after the unification of North Yemen and South Yemen and coinciding with the rapid increase in Yemen’s oil production. Currently Yemen’s oil production comes from two onshore basins (Sab’atayn and Say’un-Masilah) only, and the country’s production has been in a steady decline since its maximum production of 438,000 barrels per day in 2001. However, there are good opportunities for further oil and gas exploration and discoveries in many of Yemen’s basins. The historical perspective outlined in this paper may be of use in this direction as well.

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Professor Ziad Rafiq Beydoun who pioneered the geological studies of Yemen’s sedimentary basins and stratigraphy, including his dissertation “The stratigraphy and structure of the East Aden Protectorate,” which won him a Ph.D. degree at Oxford in 1961. Beydoun’s biography is given in the Journal of Petroleum Geology, 1998, v. 21, p. 359-360, the online Wikipedia (“Ziad Rafiq Beydoun” with photos from Mike Morton Collection) as well as in obituaries by Jim Ellis published on the website of the British-Yemeni Society (www.al-bab.com/bys/obits/beydoun.htm), by Ron Miller et al. in the IPC Newsletter (Issue 99, July 1998, pp. 36-7), Gareth Smith in The Daily Star (www.dailystar.com.lb/articles/April98/22_4_98/f.htm), and by Mohammad Darsi Abdulrahman in The Yemen Times (August 12, 2009). Since 1991, AAPG has given the Ziad Beydoun Memorial Award to the author(s) of the best AAPG poster session paper presented at the AAPG International Conference.