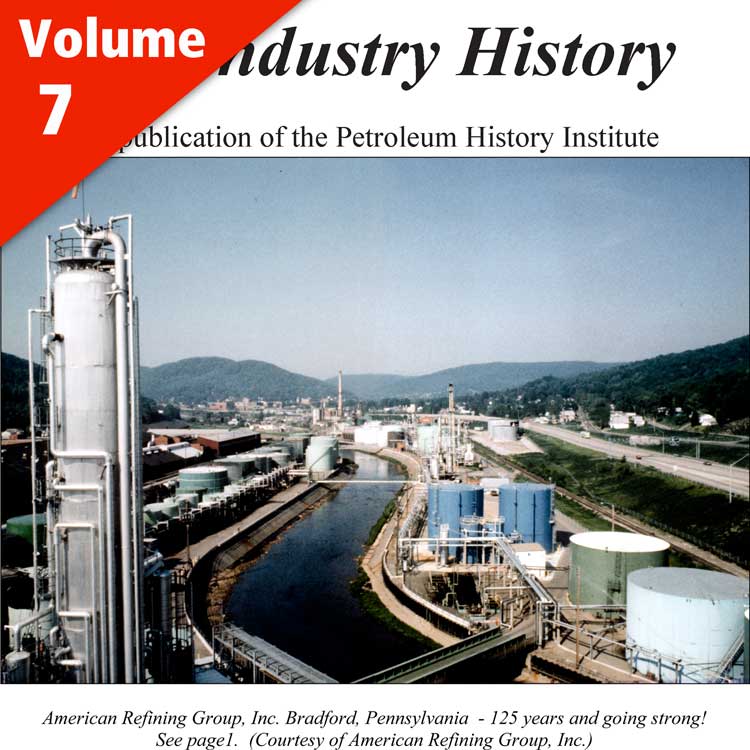

This Issue was Sponsored in Part by a Grant from the American Refining Group, Inc. and by Daniel F. Merriam

Celebrating the 125th Anniversary of American Refining Group, Inc. Bradford, Pennsylvania

and the Symposium – Wichita, Kansas – April 20-23, 2006

The Little Refinery That Could,

OIL 150: Commemorating the 150th Anniversary of the Drake Well and the Birth of the Petroleum Industry,

McCoy # 1 Is Mirrored in its Pond Near Garden City (Watercolor),

Editorial and Meeting Report,

Advances in the Science and Technology of Finding and Producing Oil in Kansas: A Critique,

A Brief History of the Kansas Oil and Gas Industry,

The Early Oil Industry of Southeast Kansas Illustrated on Postcards,

Collecting Rocks – The History of the Wichita Well Sample Library,

A Brief History of the Oklahoma Oil and Gas Industry,

A Brief Summary of Oil Industry Folklore,

Slide, Kelly, Slide – How the Roughneck Identity was Shaped Through Language, Leisure and Environment,

The Anaconda Story – A Recollection,

Abstracts – Wichita Symposium April 20-23, 2006

Historic Oil Field Tour and Oil Museum Visit,

Petroleum History Institute Awards – 2006

Volume 7, 2006 Abstracts

The Little Refinery That Could

Harvey L. Golubock

American Refining Group, Inc., 77 North Kendall Avenue, Bradford, Pennsylvania 16701

ABSTRACT: This year marks the 125th anniversary of American Refining Group’s Bradford, Pennsylvania refinery. Established in 1881, it is the oldest continuously operated refinery in the United States and the oldest in the world still refining crude oil. It is a success story, a celebration of achievement that has developed over 125 years of uncompromised commitment to quality, devotion to details and an unwavering entrepreneurial spirit. It is the story of generations of people whose ancestors started this refinery with the pioneering spirit that has made this such a great country. Today Bradford, Pennsylvania, may be known only on the Weather Channel as the coldest spot in the nation, but long before the Weather Channel even existed, Bradford was the energy capital of the United States. Oil was not discovered in Bradford until five years after the first commercial well was drilled in Titusville in 1859, seventy miles south of Bradford. The Bradford oil fields however proved to be among the most prolific of the early finds. In 1881 over 83% of the country’s oil came from Bradford. Much has been written over the years about the Bradford fields and the explosive growth of the oil industry in the region around the turn of the 20th century. ARG has commissioned a book that will be published this fall by Arcadia Publishing. It highlights the early history of the refinery with many rare photographs; a sampling of which accompany this article.

Advances in the Science and Technology of Finding and Producing Oil in Kansas: A Critique

Daniel F. Merriam, Senior Scientist Emeritus

Kansas Geological Survey, 1930 Constant Ave, Lawrence, KS 66047

ABSTRACT: The science of exploring for oil and gas and the technology of producing it are inextricably intertwined. As progress is made or refined in one area, it is reflected in the other. This symbiotic relationship is repeated in most petroleum oil-producing areas, but is well exhibited by the development of the petroleum industry in the U.S. Mid-Continent, especially in Kansas. Petroleum exploration and exploitation have a long history in Kansas dating from 1860 when the second oil well in the U.S. was drilled near Paola in Miami County. Since that time, some 380,000 wells have been drilled in the state in this mature Mid-Continent petroleum province in search of the black gold. A series of technical advances helped the Kansas oil industry stay competitive through the years: use of nitroglycesine to frac wells (1893), rotary drilling (1920s), water-flooding secondary recovery method (1935), acidizing formations (1930s), and directional drilling and CO2 injection (1990s). New exploration and exploitation techniques included surface mapping (1910s), core hole drilling (1923), single shot seismic (1923), microseismics (1950s) and 3D seismics (1970s), computer-oriented methods to process data (1963), in-fill drilling (1980s), and available large digital databases (1990s). These techniques continued to be developed, refined, and improved through the years after their introduction.

New concepts recognized that oil and gas occurred in units older than Pennsylvanian rocks (1903), and that accumulation and entrapment of petroleum was related of anticlines (plains-type folds) (1908) and shoestring sands (1917). Understanding that the Nemaha anticlinal structure had a west flank meant that there were possibilities for oil and gas production in western Kansas, especially after discovery of oil in the Fairport field in Russell County in 1923. Helium was discovered in 1906 at Dexter and the huge Hugoton gas field in 1922; the Hugoton was so large it was years before its size was defined. Economic factors in the international, national, and local economy interplayed with scientific concepts and technical advances and developments to create a swing in the Kansas petroleum industry from glut to bust and vice-versa. Kansas went from the Number 1 producing state in 1916 to number 10 in 2006. During these nine decades the price of oil seesawed from 10¢ to $70 plus per barrel.

Key Words: Exploration techniques, geological concepts, technology advances, economic factors.

A Brief History of The Kansas Oil and Gas Industry

Lawrence H. Skelton

Kansas Geological Survey, 4150 Monroe, Wichita, Kansas 67209

ABSTRACT: The presence of petroleum, or mineral oil as it was called, has been known in Kansas for as long as there have been people crossing the plains. In the report of the first State Geologist, Benjamin F. Mudge, he notes that oil seeps were known in many places across the state. After a visit to Pennsylvania in 1860 and hearing about the success of Col. Drake, George W. Brown, a Lawrence newspaperman, recalled a note in his newspaper about an oil spring in Lykins County. Brown and a local member of the State Legislature tried, unsuccessfully, to strike it rich, but there was not much oil in their wells. The operation was interrupted, and eventually closed, by the Civil War. Though not finding oil in large quantity, this was the first oil well in Kansas. In 1892, a proposed gas well financed by local investors in Neodesha, Wilson County, was drilled on riverbank land belonging to T.J. Norman, a local blacksmith. Drilling was completed and the well came in producing oil on November 28, 1892. It was capped since the desired gas was not found. William Mills, the driller, took a sample of the oil to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to see if he could raise interest in that more oil-savvy area and returned to Kansas with John Galey and James Guffey who definitely were interested. They shot the Norman No. 1 with 30 quarts of nitroglycerine hauled by wagon from Webb City, Missouri. Initial production of 12 barrels per day was sufficient to interest Galey and Guffey who proceeded to lease all the land around the town and to begin drilling. Norman No. 1, the opening well in the Mid-Continent Field, was soon followed by many more.

The Early Oil Industry of Southeast Kansas Illustrated on Postcards

Jeff A. Spencer

675 Piney Creek Rd. Bellville, TX 77418

ABSTRACT: Postcards were a common means of communication and a popular collectible in the early twentieth century. The postcard, and occasionally the sender’s accompanying note, provides a glimpse in time of the industrial growth of the United States. The Golden Age of postcard collecting (1907-1915) coincided with the oil boom of southeastern Kansas. Scenes of wooden derricks, oil gushers, oil field fires, and refineries were common themes of these early cards.

Oil derricks and gushers near Cherryvale, Independence, and Chanute and later scenes of the great Augusta (1914), El Dorado (1915), and Towanda (1917) oil fields are well represented on early postcards. The famous 1906 Caney burning gas well disaster, turned tourist attraction, is depicted on postcards claimed by the towns of Independence, Coffeyville, Bartlesville, and Caney. Come and see the wonderful gas well states the sender of one of these Caney postcards. Postcards document the early petroleum refining industry’s growth in Kansas, including the Standard Oil refinery in Neodesha and the National Refining Company in Coffeyville. Oil tank fires and oil Company towns, such as Oil Hill – the town that oil built, were also depicted on postcards.

Collecting Rocks – The History of the Wichita Well Sample Library

Lawrence H. Skelton

Kansas Geological Survey, 4150 Monroe Street, Wichita, KS 67209

ABSTRACT: For more than a century, geologists have more or less routinely performed visual and microscope examination of rock cuttings recovered from oil and gas wells. During the first two decades of the Twentieth Century, the market for refined oil products swelled and the numbers of wells drilled grew commensurately. Oil companies and consulting geologists began to trade well cutting samples and other associated well data and many maintained private sample collections.

In Kansas, then the third or fourth most active state for exploration and drilling, efforts to establish a sample library for use by any geologist began in the mid-1920s. Those efforts came to fruition in 1938 with establishment of the Kansas Geological Survey’s Wichita Well Sample Library. The Sample Library, now in its 68th consecutive year of operation has expanded its scope over the years and now holds rock cutting samples from approximately 133,000 oil and gas wells. In the midst of the current boom, an average 58 wells per month are being added to the collection which is regularly used by both in-state and out-of-state clientele.

The Conroe Crater

Kristin L. Wells

1201 15th St. NW; Suite 300, Washington, DC 20005

ABSTRACT: Men and technologies converged to rescue an oilfield near Conroe, Texas. Strake Well Comes In. Good for 10,000 Barrels Per Day proclaimed Conroe Courier headlines in June of 1932. George W. Strake had discovered the 19,000-acre Conroe oilfield, but its geology made drilling and development risky. Six months later, Standard Oil of Kansas’ Madeley No.1 blew in as a gusher and immediately erupted into flame. All attempts to put out the fire with dynamite blasts and tons of dirt failed. The crater spread into a growing lake of burning oil, and the entire field was threatened. The nearby rig of Jim Abercrombie and cousin Dan Harrison collapsed into the growing crater. With its casing shattered, their well unleashed the reservoir’s full fury and millions of barrels of oil began surging into the crater. Enid, Okla., entrepreneur George Everett Failing and his crew were working near Conroe. Failing had begun his company only two years prior when he mated a drilling rig to a 1927 Ford farm truck and a power take-off assembly. While a traditional steam powered rotary rig took about a week to set up and drill a 50-foot borehole, George E. Failing could drill ten 50-foot holes in a single day. Working behind walls of Foamite and sheets of asbestos to suppress the flames, Failing drilled nearly a dozen 600-foot relief wells in record time, enabling the firefighters to at last extinguish the inferno. But the growing lake of oil continued to feed off of the sunken Abercrombie and Harrison casing at the rate of over 6,000 barrels each day. Meanwhile, reduced pressure in the field dropped all other wells to less than 100 barrels per day production. Humble Oil Co. was determined to bring the well under control before it drained the field and completely destroyed their investment. In an effort to choke off the unrestricted flow of oil into the crater, Humble Oil brought in H. (Harlan) John Eastman. Today, he is recognized as the father of directional drilling and surveying in the United States but in 1933, his techniques were new when put to the test in Conroe. Thanks to Eastman, by January 1934, a local newspaper reported, Conroe Crater Becoming Just Another Well.

A Brief History of the Oklahoma Oil and Gas Industry

Lawrence H. Skelton

Kansas Geological Survey, 4150 Monroe, Wichita, Kansas 67209

ABSTRACT: The first oil well in Oklahoma was drilled the same year as the Drake well in Pennsylvania, but unlike Drake, this was to be a brine well, not an oil well. The oil was neither sought nor wanted at the time. Not until 1890 was another well drilled, this time for oil, and that really started the Oklahoma oil boom. As wells were being drilled in nearby Kansas, speculators began expanding into the then Oklahoma-Indian Territory. The railroad came to Bartlesville in 1899 and provided transportation of the oil to Caney, Kansas, where it entered into a pipeline which took it to the Standard Oil Refinery at Neodesha, Kansas. The Bartlesville-Dewey discoveries added to a growing fever to find oil in Oklahoma. The immense Burbank Field was discovered the same year and has remained active for more than a century with accumulative production exceeding one-half billion barrels. Not all the great finds were centered in northeastern Oklahoma. The hilly, rugged southern part of the state around the Arbuckle Mountains had its share too. Carter County’s Healdton Oil and Gas Field was discovered in 1913. Some of the wells came in at 5,000 barrels per day and gas wells presented daily capacities of 40 million cubic feet. Maximum oil production was during 1917 when the Healdton produced 22.5 million barrels. By the end of 1919, there were 2,070 producing oil wells and an accumulative amount near 126 million barrels had been produced from the field’s 13 square miles. And the potential is still there. The Anadarko basin west of Oklahoma City is one of the nations’ few underdeveloped hydrocarbon reservoirs. The Cherokee Shelf, which contains the older fields of northeastern and north central Oklahoma extends from exposed surface strata to granite a few hundred feet below the surface at the Arkansas state border.

A Brief Summary of Oil Industry Folklore

Herman K. Trabish

2763 Mary Street, La Crescenta, CA 91214

ABSTRACT: Sometime in the late nineteenth century, There’s GOLD in them thar hills!” transmuted into There’s OIL out there! As the oilfield pioneers left the Pennsylvania and Baku regions and took the industry to the farthest corners of the world, they created their own legends and lore. The premier chronicler of oil’s lore was historian and folklorist Mody Coggin Boatright. Building on field research which recorded the realities of oilfield life, he documented the tales that grew around the realities and how they grew taller as time passed. If not every well came in, each had its story. Real people transmuted into indelible character types. Finally, the real life of Gilbert Morgan of Callensburg, Clarion County, Pennsylvania, gave forth Gib Morgan, the greatest oil industry hero of them all.

Slide, Kelly, Slide: How the Roughneck Identity was Shaped Through Language, Leisure and Environment

Bari A. Sadler

Department of History, Texas Tech University, Box 41013, Lubbock, Texas 79409

ABSTRACT: In the past, historians have overlooked the importance of labor in the oil industry. This was caused by a focus on industrial and agricultural labor. Soaked in blood, sweat and black gold, the roughneck began to symbolize blue collar identity for many Americans. Using the Borger, Texas Boom as the context, this paper will demonstrate how this identity evolved during the period from 1925 to 1940.

One factor that made the Panhandle-Plains boom different from previous booms was the isolated nature of the production sites. With no trains or pipelines, everything had to be trucked in and out of the area in the beginning. Also, without the advantage of strong labor unions, the roughneck culture evolved very differently from that of the factory and field worker. Even with the obvious differences, his agrarian background played a major role in shaping his identity. In this way, the boll-weevil apprentice became the seasoned hand. Educated by experience, he was a necessity in the oil field. The roughneck shaped his identity through jargon and attitude. He could work harder for a longer period of time than anyone. He also played hard. Commercial leisure venues ensured that there would always be a place for him to unwind. During the Depression, roughnecks always had money to spend. This created a catalyst for the sprawling dancehall environment that emerged in Borger.

By examining these areas of language, leisure and environment, we can truly define the roughneck and the exciting world he occupies. It is through the roughneck that we envision the foundations of a new type of wage laborer and the difficult struggle with the environment that took place.

The Anaconda Story: A Recollection

Samuel T. Pees

Wesbury, 31 Park Avenue, Meadville, PA 16335

ABSTRACT: Every oil geologist who has ever worked in the field, especially in tropical regions of the world, has a snake story, or two. Mine occurred in eastern Peru in 1958 when I was mapping the surficial geology while working for the Texas Petroleum Company. I was working with Dr. Bernhard Kummel of Harvard University and a consultant for Texas Gulf Producing Company at the time.